Hurricane Idalia has moved on, but an invisible threat remains in its wake — health officials are urging millions of Labor Day weekend beachgoers to be aware that floodwaters left over may contain Vibrio vulnificus.

The rare and potentially deadly type of flesh-eating bacterium “shouldn’t be taken lightly,” Florida Health Department press secretary Jae Williams said. “It needs to be treated with proper respect — the same way we respect alligators and rattlesnakes.”

Florida health officials started warning residents of the potential for such bacterial infections “as soon as the state of emergency was declared,” Williams said.

Coastal areas of the state, as well as Georgia and the Carolinas, where Idalia’s surges left behind standing water, were most at risk for Vibrio bacteria.

Vibrio thrive in estuaries, inlets and other areas of warm, brackish water that combine ocean water and freshwater. Hurricanes are good at creating these conditions.

Idalia’s storm surges, for example, forced the salty seawater onto land, where it was met with heavy rain.

“The rainwater, being freshwater, dilutes the seawater and brings the salinity down,” said James Oliver, a retired professor of microbiology at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. That mixture creates the perfect condition for the bacteria to thrive and spread.

There are several types of Vibrio, but V. vulnificus are the most dangerous.

The bacteria infect an estimated 80,000 people in the United States every year, killing about 100, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Those numbers tend to rise in the wake of hurricanes.

It’s a phenomenon that’s been reported during previous hurricane seasons. In the week before Hurricane Ian hit Florida last year, there were no cases of Vibrio infections in the area where the storm made landfall. The week after Ian stormed through, 38 people became infected. Three people had to have at least one leg amputated, and 11 died.

Similar increases were seen following Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

How do Vibrio infections occur?

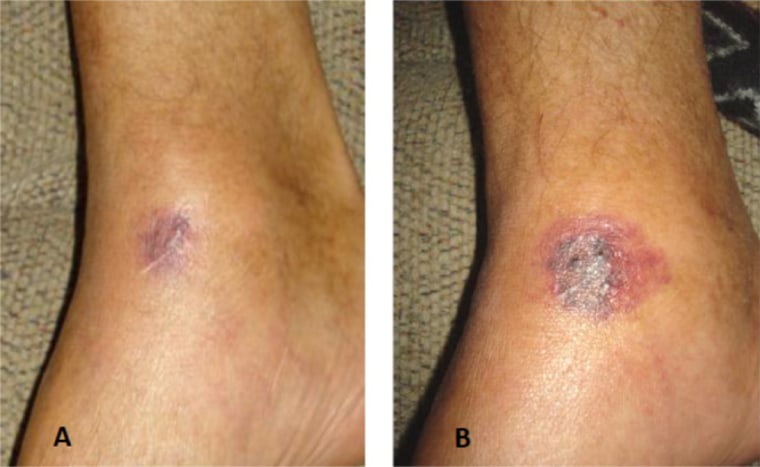

The bacteria enter the bloodstream through a cut in the skin, usually on the foot or ankle as people wade through water. Once infected, people “get a little lesion that looks maybe like a spider bite,” Oliver said.

But very quickly, the bacteria start destroying the surrounding tissue. The incubation period, he said, is about 16 hours.

The wound gets larger, redder and more painful. It is critical to seek medical help and get started on antibiotics as fast as possible. “Speed is essential. These are the fastest growing bacteria known to man,” Oliver said.

Amputations may be necessary to stop the bacteria from spreading elsewhere in the body. In some cases, patients have been known to die within a day of exposure.

Eating raw oysters is the second way people become infected. Oysters eat their food by filtering water through gills.

“Just realize that you’re eating a live animal and you’re eating the intestinal contents of whatever it ate, which typically is Vibrio,” Oliver said.

Rising Vibrio cases

Vibrio tend to be most active between May and October, usually in the warmer waters of the southeastern coast of the U.S., including parts of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana and Mississippi.

But Vibrio infections have begun to pop up earlier, later and farther away than expected.

“The chances of getting it are increasing because it’s spreading geographically and in larger numbers because of the warmer waters,” Oliver said.

Last month, it was reported that three people in New York and Connecticut died from Vibrio infections.

Afsar Ali, a research associate professor in the department of environmental and global health at the University of Florida, said he has noticed Vibrio infections becoming more common during the past five years.

“I have seen the increasing numbers of Vibrio vulnificus cases,” he said. “Every year, it is increasing.”

In addition to rising water temperatures, Oliver noted, climate change is increasing the risk for Vibrio to thrive in another way.

Vibrio “will not grow or survive in full-strength seawater,” he said. “But because glaciers are melting, it’s decreasing the salinity of seawater.”

Who is most at risk?

Millions of people wade in brackish water and throw down raw oysters every year without any problem.

But some groups appear to be more susceptible to Vibrio infections: men over age 40 and those with underlying health problems, especially liver disease.

When the liver is damaged, it can increase levels of iron in the blood. And Vibrio bacteria “love to eat iron,” Ali said. They use it to “just march on through your tissue, destroying everything they encounter.”

The risk for these groups is much greater when exposed to Vibrio vulnificus through raw oysters, Oliver said.

“If you are a male over the age of 40, and you know you’ve got some liver disease, you want to avoid raw oysters like the plague,” he said.

How to stay safe

Cooking oysters destroys the bacteria, making them a much safer option for consumption, experts say.

But for beachgoers, there is likely no way to avoid Vibrio.

“It is virtually guaranteed that if you wade into coastal waters this weekend, you will encounter such bacteria,” Oliver said. “While that is a scary statement, it is important to understand that the risk for becoming sick from that encounter is extremely low for the vast majority of people.”

If people have open wounds, they must cover them completely before entering brackish bodies of water or stay out of them.

“If you’ve got any sort of wound on your leg or develop a wound while you’re at the beach, you really want to try to protect yourself and not expose yourself to water in those cases,” said Dr. Rachael Lee, an associate professor in the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“If you don’t have wounds, then the risk of wading in the water is practically zero,” she said.

This story originally appeared on NBCNews.com.

Read the full article here