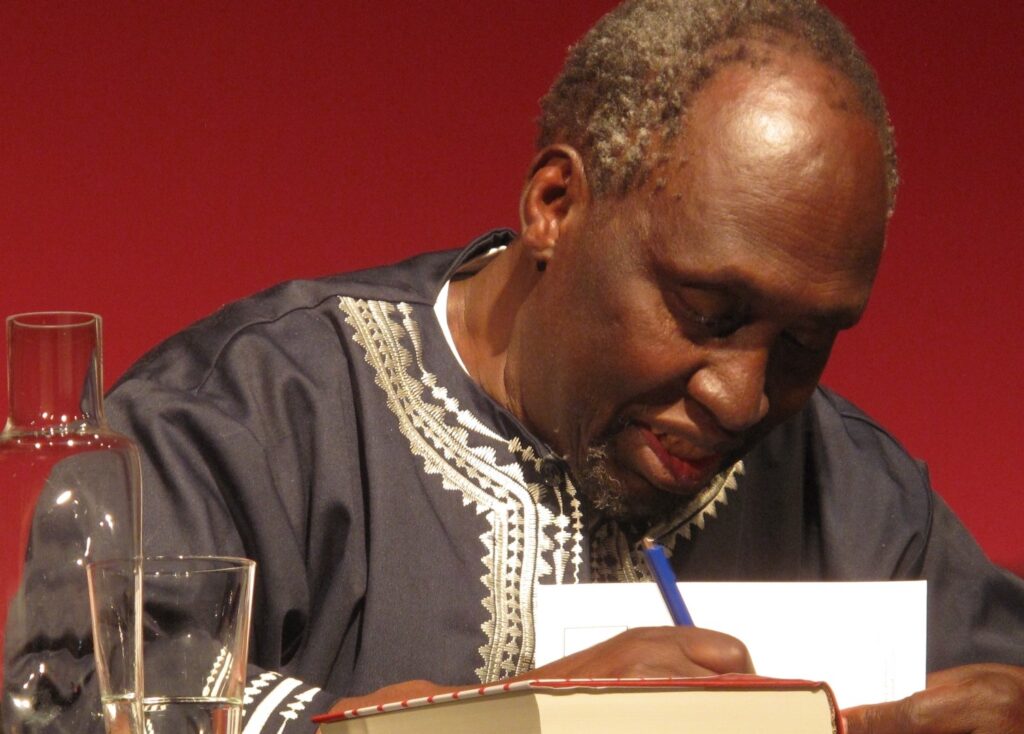

On March 12, Mukoma wa Ngugi, the Kenyan American poet and author, who is the son of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the famed writer widely seen as a giant of African literature, took to X, formerly Twitter, to allege that his father was an abusive husband.

“My father Ngugi wa Thiong’o physically abused my late mother. He would beat her up. Some of my earliest memories are of me going to visit her at my grandmother’s where she would seek refuge.”

Mukoma’s tweet went viral and solicited hundreds of responses that exposed the long, dark shadow patriarchy continues to cast over many African societies.

Sure, many commentators thanked Mukoma for sharing his account of a man who is not only his father, but an African cultural icon.

Others, however, were less complimentary and appeared to be gravely offended by his openness. They accused him of embarrassing his father and seeking validation from Westerners.

Mukoma’s assertions, some claimed, was a “consequence of Western education”. It is, they suggested, “un-African” to speak out against one’s father, more so to thousands and potentially millions of strangers.

Ten days after his initial statement, on March 23, Mukoma responded to the criticism he received for speaking up for his mother.

“We cannot use African culture to hide atrocities,” he wrote on X. “My father beat up my mother. What is African about that?”

In another post, he described the culture of violence against women that underpins Kenyan society as a “patriarchal cancer”.

Ngugi is a literary genius, a storyteller par excellence and a respected revolutionary.

Before there was the internet, video on-demand platforms, TV or even radio in most households, two African giants dominated African literature: Chinua Achebe, the Nigerian author, and, of course, Ngugi.

From the 1960s, Achebe and Ngugi articulated African identity and consciousness amid the anti-colonial struggle.

They stood up for the human rights of Africans with their words.

Through novels like Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God, to name a few, Achebe chronicled the impact of colonialism on Igbo culture, religion and sociopolitical systems. And in a Man of the People, he explored the failings of postcolonial leadership and states.

Ngugi, who went by the name James early in his career, also focused on African opposition to colonial rule. Weep not Child, for instance, deals with the so-called Mau Mau Uprising, while Grain of Wheat looks at the state of emergency in Kenya’s struggle for independence (1952–60).

Through these and other novels, Ngugi advocated for resistance against colonial oppression and repression in the independence era.

In 1978, he was arrested and detained for a year without trial by the administration of former Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta over a play titled Ngahlika Ndenda (I will marry when I want).

Over the years, Ngugi was regularly harassed and victimised by authorities in Kenya for voicing his opposition to corruption, misrule and the abuse of power.

He has stayed the course and today, at the age of 86, continues to advocate for freedom from neocolonialism and political oppression.

With 13 honorary degrees from institutions around the world, as well as countless awards, including the 2022: PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature, Ngugi is a certified literary genius.

But, for all of his achievements in the last 60 years, the famed author appears to have failed where it counted most: protecting African women.

He produced many timeless literary classics, and became a leading voice in the fight against colonialism and post-colonial repression, but according to his own son, could not liberate his dear wife, sons and daughters from the extreme ravages of toxic masculinity and domestic violence.

Of course, in the wake of Mukoma’s public disclosures, Africans could choose to label Ngugi a flawed genius. He is, after all, human.

They could – as many tried to do in lashing out at Mukomo – brush his alleged abuse of his wife under the carpet in the name of protecting his literary and revolutionary legacy.

This would be an easy and convenient position to take.

But it wouldn’t be right.

Ngugi’s alleged personal failings, sadly, are not only his own. The harm he is said to have inflicted on his wife is not the unique failing of a genius. It is very much representative of a societal ill pervasive in most African populations. It is proof that even the most respected and principled revolutionaries, who have been consistent and relentless in their defence of human rights and dignity on the surface, are not immune to the ill effects of patriarchy.

Ngugi, it seems, wanted women to experience liberty from colonialism and post-colonial subjugation, but remain bonded to the steely constraints of Kikuyu culture.

Although he repeatedly expressed how he abhorred systemic violence, he apparently believed he had the “right” to consistently employ violence against his spouse and, by extension, his children.

To his mind, it seems, there were limits to women’s human rights.

For a long time, under the guise of tradition, African men have been allowed and even encouraged to discipline “their women” and children with violence.

Thus, many argue Ngugi is just a product of his times and what he is said to have done to his late wife should not be judged through a 21st-century progressive lens.

The truth, however, is that gender-based violence is not a practice of old. It is very much a modern and everyday menace in African societies. And it can never be tackled if we continue to excuse the actions of abusers, especially those with high public profiles, by pointing to their age, their professional success, or indeed, seemingly impeccable anti-colonial and revolutionary credentials.

The spirit of intolerance and violence that “allowed” Ngugi to physically assault his wife in the 1960s and 1970s has not dissipated.

In fact, gender-based violence is on the rise in Kenya.

On January 27, thousands of protesters, male and female, took to the streets of Nairobi calling for an end to femicide and violence against women.

About 500 women and girls have been murdered in Kenya since 2016.

According to a report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and UN Women, “Such homicides are usually the fatal endpoint of a pattern of physical or sexual violence, fuelled by social norms enforcing male control or power over women.”

Ngugi’s alleged violence is, unfortunately, a window to a continental (and, frankly global) problem.

Hence, his son’s revelations should not become a point of contention.

This should instead be a teaching moment.

How do our cultural practices and norms intersect with modern or constitutional rights and liberties?

Is culture beyond the purview of transformative change?

The struggle from oppression, I must say, is far from over.

Much good can still come out of this undeniably sad episode in Ngugi’s life.

As someone who is still active in public life, the famed author can finish telling the story his son started, acknowledge his shortcomings, and publicly apologise for the pain he allegedly inflicted on his wife, Nyambura, and his entire family.

I understand that this won’t be an easy feat, but it is perhaps the only way for the author to protect his revolutionary legacy, and take his lifelong fight against oppression and injustice to another level in his sunset years.

As an agent of change who commands widespread respect, he should own up to his failings and spread greater awareness about the need to free women from the bonds of depraved cultural norms.

It is time to assess how certain traditions pose a threat to women’s wellbeing and indeed their very lives.

Our understanding of the behaviours that make an African man must change.

For too long, violence and intolerance against female agency have been used as markers of masculine pride and authority in Africa.

It is time to say enough is enough.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

Read the full article here